Author: Hoang Giang – Vietnam Agriculture

On February 15 in Hanoi, the Center for Agricultural Research and Ecological Studies (Vietnam Academy of Agriculture) in collaboration with De Montfort University – United Kingdom, Department of Science, Technology and Environment (Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development), a number of units under the Vietnam National University of Agriculture (VNUA) and the Institute of Sociology organized an international conference with the theme “Resilience of the agricultural supply network in Vietnam”.

Making the opening speech, Dr. Pham Van Hoi, Director of the Center for Agricultural Research and Ecological Studies (CARES), said: “Population growth, globalization, and urbanization have led to huge fragmentation in the global agricultural supply chain. Environmental degradation and associated consequences such as epidemics, natural disasters, and conflicts between countries have caused supply chains to be interrupted or broken. This means that, in face of environmental problems and related disasters, we will be able to witness the supply chains becoming more and more fragile. This is also an issue that De Montfort University research with great focus, looking for solutions to strengthen the sustainability of the agricultural supply chain in the local model in particular and on a global scale in general”.

Limitations for both traders and farmer households

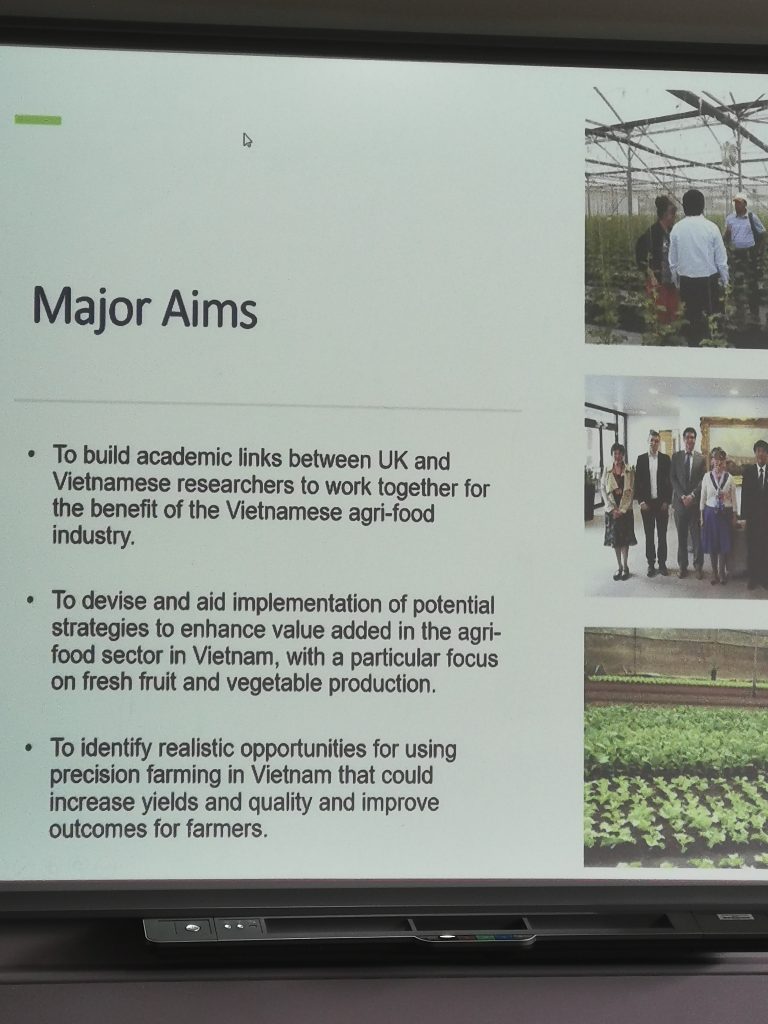

Sponsored by the British Academy, the project “Agricultural trading network in Vietnam” is implemented by a research team including Dr. Luong Tuan Anh of De Montfort University, Dr. Ngo Trung Thanh of CARES, and experts from 2020 to the present date. The goal is to establish a database on the distribution system of agricultural products specifically vegetables in Hanoi, quantifying the adaptability of the agricultural product trading network, finding out the causes of the underdevelopment of the network, thereby proposing measures for the actors in the network.

The survey was conducted in three localities, including Van Hoi commune (Tam Duong district, Vinh Phuc province), Van Duc commune (Gia Lam district, Hanoi), and Coi Ha village, Pham Tran commune (Gia Loc district, Hai Duong).

The results of the analysis and evaluation show the diversity in the trading network in the three communes, however, the ability to recover the agricultural product trading network remains low. On average, each household has less than two traders coming to conduct trades (1.7 traders/farmer household). A majority of households have limited ability to negotiate prices because there are not many channels to sell to traders. This leads to many risks in case traders cannot connect with households or do not purchase, making farmers unable to sell goods, directly affecting production and income.

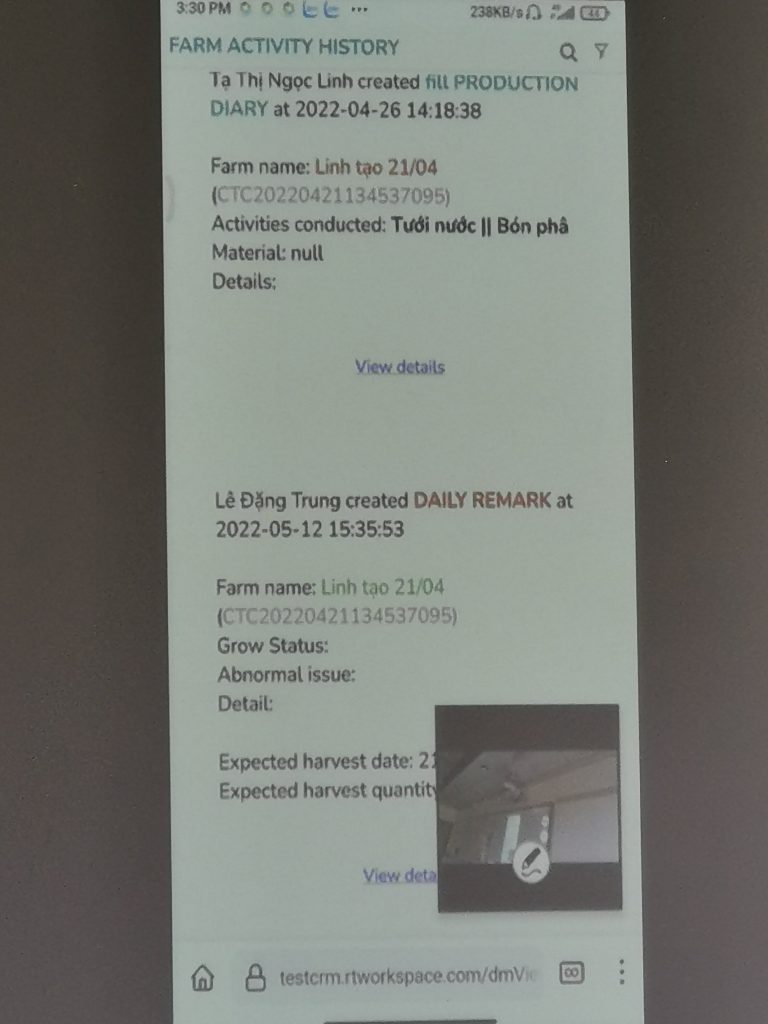

Regarding some obstacles when expanding the distribution system, research shows that it takes traders a long time to work with farmers, while farmers tend not to work with many traders, driving mainly due to aversion to risk. Most of the traders only work with less than ten households because the cost to expand the distribution network is considerably large, thus solutions are required in order to increase the interaction between farmer households and traders, in which digitization can be considered an effective option. Instead of traders having to visit each field for inspection, farmers can provide pictures of the production area and production process on an electronic system. Traders can observe and evaluate field quality on the platform.

“It is essential to help reduce people’s tendency to be afraid of risks, help them realize the importance of developing a network of agricultural products, thereby expanding their relationships with traders,” said Dr. Luong Tuan Anh.

More in-depth and longer-term research is needed

A representative of the Department of Science, Technology and Environment shared some ideas with the conference after listening to the research results. “In Vietnam, agricultural supply chains are generally shaped based on the main product. In a chain with too many products with different values, it will be difficult to visualize the stability of the chain during operation. Taking the example of the surveyed subjects, if we do not clearly divide the key agricultural product groups of each region, we will not be able to clearly see the impact of the product on the whole chain.

“Particularly in this case, there are many types of vegetables, and each type’s form and scale of cultivation possesses certain distinctions, so the effects of each group on farmer households are also very different. Because of the limited sample data, it is possible to divide the survey results into several main groups, from which the research results, risk assessment and policy recommendations will become clearer.”

According to Dr. Hoang Sy Thinh (Faculty of Accounting and Business Administration, VNUA), the research at present mainly refers to the purchasing system, production households and traders but still has its limitations as the project has yet to establish a clear framework. “The study gives data of 1.7 traders/farmers and regards this number as difficulty and limitation, but the question is what standard helps us to confirm that thesis.

There are some systems that don’t need a trader in reality. Farmers can join cooperatives or small chains, such as the self-sufficiency movement that helps reduce inventories, emissions in farming or information asymmetries. Vegetable farmers around Hanoi can join communities and supply directly to apartments. Therefore, it is deemed necessary to establish a specific framework to determine the research direction in accordance with marketing resilience, market resilience or distribution chain resilience, then the research’s future implementation will be clearer”.

The link of the article can be found here